Against Proof

by Florence Yee

In the early 2010s, vintage queer photographs made the rounds on tumblr. The implications of suggestive looks, hand-holding and eccentric dress inspired an Internet generation to form histories of kinship and resilience amid public silence. However, to the chagrin of thousands of queer youth, a quick reverse image search easily revealed that these images were constructed—fakes.

These cases dance around in my mind when I parse photo archives of Chinese-Canadian women. I pause most often on images of school dances, family outings and young friendships. What am I looking for?

We demand evidence of our communities, often for good reason: to imagine ourselves in a larger narrative; to understand our lineages and legacies; to affirm our belonging, conditional as it may be. And yet, even as queer and racialized people are gravitating toward archival practices—from which we were once excluded—the form of the archive itself still retains the structure of the problem: their inherently limiting boundaries of authority, (in)accessibility, ethnographic classification and a penchant for legible representation. How do we hold space for the unrecorded, the unrecordable, and the yet-to-be-recorded? What if our desire for documentation might be damaging? The challenges of commemoration beckon me to consider what queer theorist Jack Halberstam refers to as “new forms of memory that relate more to spectrality than to hard evidence, to lost genealogies than to inheritance, to erasure than to inscription.”

I saw these ideas unfold in the exhibition Presence is Absent / Absence is Present, which took place in 2019 at Centre Never Apart in Montreal. It was spurred by the 50th anniversary of the decriminalization of homosexuality in Canada, a time not necessarily for celebration, but for reflection. Curated by Véronique Boilard, Virginie Jourdain and kimura byol-nathalie lemoine, the show was the culmination of months of research by a group of twelve artists/archivists/activists in partnership with the Gay Archives of Quebec.

The archives are a place of wonder, longing and disappointment, messily blended together in pH neutral boxes. Although the exhibition is rich in photographs of parties and newspaper clippings, the archivists saw that there were glaring holes with regard to trans lives, everyday struggles, communities of colour, and sapphic love (to name a few).

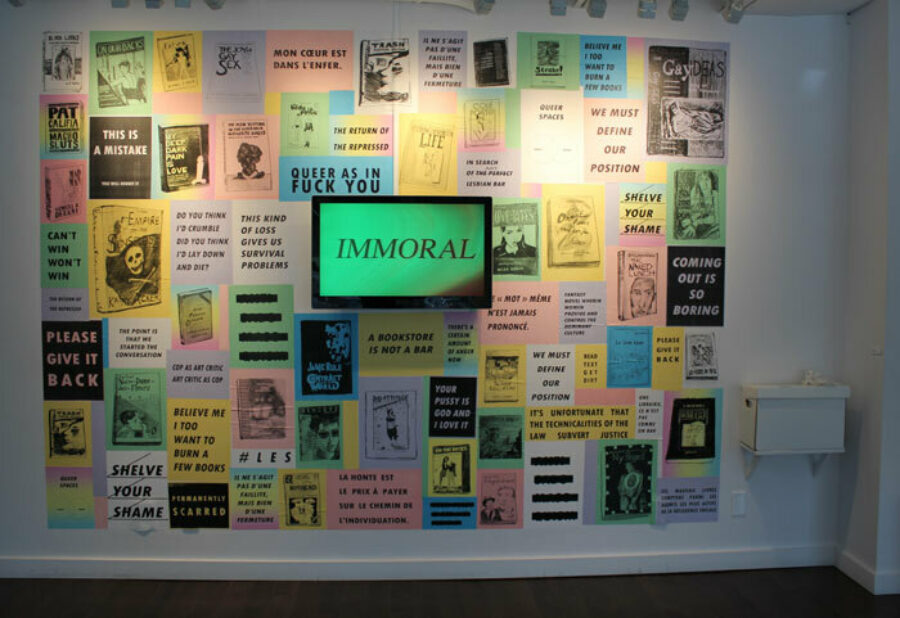

In defiance and honour of these absences, two pieces in the exhibition stood out for me. The first was A Bookstore is Not a Bar, a multi-media installation by Jenny Lin and Eloisa Aquino. Hand-drawn covers of books banned at Canadian borders for their queer content form a thought collage alongside song lyrics and phrases from queer politics. They surround a digital screen that scrolls through words used to describe this literature in cheeky fonts that overlap neon graphics. The books include titles such as black looks: race and representation by bell hooks and Empire of the Senseless by Kathy Acker. These graphite renditions remind the viewer of art and information’s materiality, capable of being inspected, censored and stopped at borders. The manual reproductions speak of what is now an absence--queer communities are even more difficult to form and maintain in the aftermath of queer bookstore closures. The hand-drawn dust jackets and slogans create a haunting more visceral than the archival originals. Phrases such as THIS KIND OF LOSS GIVES US SURVIVAL PROBLEMS and CAN’T WIN / WON’T WIN destabilize our notions of queer liberation. They are a denial of triumph, in favour of the messy and necessary everyday struggle.

A publication called Efebia and another wall of assembled pictures put together by Kinga Michalska were around the corner from the collaged installation. At first glance, the flash photography, patterned fashion and grainy images might situate the magazine in the early 1990s. On closer inspection of the printing information and the accompanying text, the viewer finds the work’s origins: a speculative (re)creation of the magazine Efebos: The First Polish Magazine of Male Nudes, that was planned to have been released in Poland in 1991. During their residency at the Gay Archives of Quebec, Michalska found ads promoting the launch, but could not find the actual printed material. After a trip to the Lambda Warsaw Gay Archives, they confirmed that the project had never come to fruition. Efebia is then an exercise in imagining and conjuring that Michalska describes “as a tribute to all the great queer DIY activist initiatives that failed—the art projects that were abandoned and collectives that fell apart before their first action.” The ensuing photoshoot was organized in Warsaw, accompanied by an open call for submissions by lesbians, bisexual women, and queer, trans and non-binary folks. As the final act in this project, a copy of Efebia was deposited in the 1990s section of the Warsaw Gay Archives.

These two projects demonstrate the potential for unfinished business, a state that necessitates vision, collectivity and playfulness. Maybe those “fake” tumblr posts had it right all along. After all, my partner happily told me that their lack of authenticity did not matter to her. Falsified evidence could well open more doors than a limited truth.