To call it a new phenomenon would be an easily refutable claim. Since her death in 1962, Marilyn Monroe has proved an alluring subject for artists and writers of successive generations. To this day, Monroe’s singular iconicity and status as a sex symbol make her an enduring vessel for artistic explorations of fame, beauty and image reproduction. My earliest encounter with Monroe was via a coffee table book that belonged to my mother. Simply titled Marilyn and written by Gloria Steinem (herself likely the most well-lit feminist writer of the 20th century), the text portrays Monroe as a deeply empathic woman whose life was often dictated by her status as an object of male desire. Steinem’s essay was an early (though not the first) feminist appraisal of the actress, whose polarizing portrayals of stereotypical bimbos and vulnerable public persona both repel and attract such a lens. I revisited the essay after encountering several recent works which used Monroe as a motif, curious about her migration in the cultural canon and compelled to examine the specifics of her current appeal in these artists’ works.

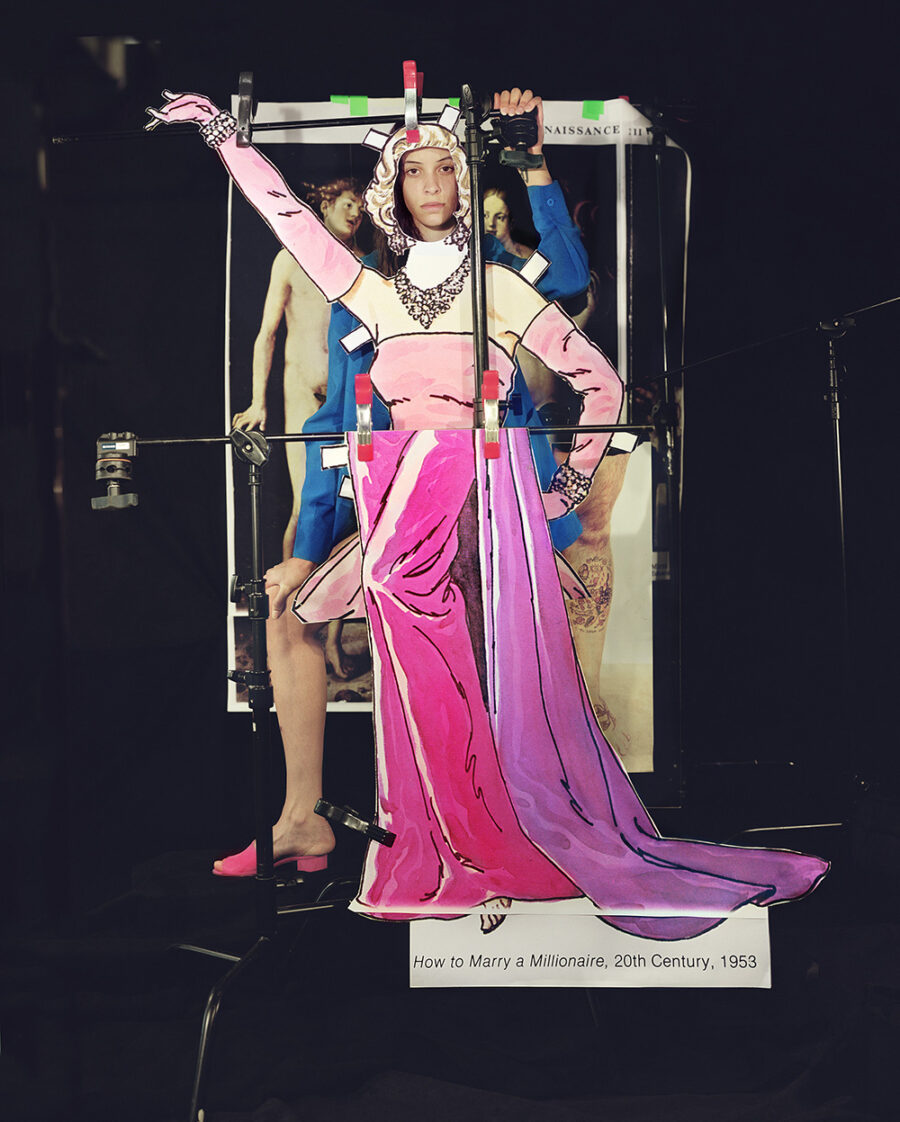

Earlier this year I reviewed an exhibition by visual artist Sara Cwynar that incorporates several allusions to Monroe, a recurring fixture in Cwynar’s practice. As she explains, her infatuation with Monroe is rooted in a morbid anecdote about the actress's chest x-rays selling at auction for $45,000, citing that even the inside of her body was up for grabs and referring to this as “an apt metaphor for the way we live now.”[1] Cwynar’s comment would suggest that the exceptional demand to consume Monroe has, in the present era of the commodified self, warped into a relatable attribute of the actress. A recent exhibition at Platform Centre for Photographic + Digital Art, The Ideal Make Body by artist Elise Dawson, featured appropriated images of art history and famous figures reauthored as selfies through some skillful doctoring. One such image features the artist-as-Monroe, a reference that feels particularly at home in Dawson’s practice, which plays upon the performance of identity and gender with a keen eye toward idealized representations of the latter. In the same vein, artist Sin Wai Kin (FKA Victoria Sin) adopts Monroe’s trademark Hollywood glamour in their drag performance and video art, donning prosthetic curves, a blonde wig and cartoonish makeup. Wai Kin’s alluring parody of Western ideals follows the hyperfeminine signifiers of beauty standards to exaggerated conclusions. Much like Cwynar and Dawson’s appropriations, Wai Kin’s parody of Monroe’s bombshell aesthetic elicits similar questions as to the politics of beauty, gender, and desire.

Elise Dawson, An earthly, sexy-looking angel! Sent expressly for me!, self-portrait as André de Dienes’ photograph of Marilyn Monroe, digital photograph, 24” x 18”, 2020

Over the span of writing this piece, Andy Warhol’s portrait of Monroe sold for a record-breaking $195M US, and meta-celebrity Kim Kardashian donned the dress that Monroe wore when singing “Happy Birthday” to JFK for the Met Gala. The perpetual frequency of Monroe’s presence in the spotlight makes it tricky to identify the nature of her specific relationship to any given moment in time. So long as she remains such a powerful conduit for the feminine ideal, each succeeding wave of feminists will likely be compelled to contend with her as a subject. What strikes me about the current iterations of the Marilyn complex is that despite (or maybe because of) her continued fame, these artists have—on some level—identified with Monroe.

Discussing what compelled her to write Marilyn, Steinem explains that she wanted to “take away the fantasy of Marilyn and replace it with reality.” Reiterating her stated imperative, Steinem’s dedication reads “to the real Marilyn. And to the reality in us all.”[2] It’s a phrase that must read differently today than when it was written.

Dawson, Cwynar and Wai Kin have engaged Monroe’s memory with a compassion similar to Steinem's. However, unlike Steinem, they seem far less invested in upholding the diametric poles of fantasy and reality. In an email correspondence with Dawson, I inquired about the Monroe image in their show, and they replied that they were “attracted to this photograph of Monroe with her eyes closed–it’s this quintessential transitional moment, where Norma Jeane [Monroe’s given name] is shifting into the performance of Marilyn Monroe.”[3] As the boundaries between our online and offline selves dissolve, it appears that fantasy and reality can no longer be considered mutually exclusive. In an era of increasingly blurred lines between the two, as we digitally perform ourselves daily on social media, the combined weight of Monroe’s legacy as both Marilyn and Norma Jeane seems more relevant than ever.

[1] Gem Fletcher, “The influence of technology and vested interests of corporate agendas is visualised in Sara Cwynar’s latest work,” 1854, June 10, 2021, https://www.1854.photography/2021/06/sara-cwynar-glass-life/.

[2] Gloria Steinem, Marilyn (Henry Holt & Co: New York, 1986), v.

[3] Elise Dawson, email correspondence, June 3, 2022.

Madeline Bogoch is a writer and film programmer based in Treaty 1 territory/Winnipeg. She is the Manager of Media Collections at Video Pool Media Arts Centre and senior programmer for the Winnipeg Underground Film Festival (WUFF), and has curated screenings with Vtape, VUCAVU and Video Pool.