In the past few years, brown, hairy bodies have come to the forefront of my virtual experience, with artists like Ayqa Khan, Seema Mattu and Alok Vaid Menon leading the charge, while other networked individuals are witnessing and circulating embodied stories of their own. There is a general feeling that brownness, blackness, Indigeneity, disability, femaleness, queerness—visible and invisible markers of difference existing in the shadows of the neutral subject, that which is white, straight, male, and able bodied—are leaving the margins and slowly approaching the centre. It can be tempting to see this emerging matrix as a progressive change in the otherwise unhappy chain of history. But as we, the networked, continue demanding online space for diverse bodies and conversations, it is essential to match this optimism with an activated memory of the Internet’s racist and imperialist framework.

Since its inception, the Internet has been coded as a utopic space free of worldly chaos, and the natural next step for mankind in his evolution. This sentiment was echoed in the very beginning of online communities, or online bulletin board services (BBS) as they were called in the 1970s, by American programmer John James who advanced the idea that virtual communities were, “a radical transformation of existing society and the emergence of new social forms. The promissory and quasi-spiritual rhetoric, formulated by the first pioneers, continued to inform the way the online space and communities were absorbed into the everyday life of people. In a popular and oft-criticized TV commercial titled “Anthem”, released by Media Control Interface (MCI) in 1997, a cast of colourful characters take turns citing, “There is no race, there is no gender, there is no age … there are only minds. Utopia? No. The Internet.”[ii] This motto is significant, for it clearly outlines the problem at stake: to enter the utopic space of the Internet we must forfeit our race, gender and age. However, for those that exist outside the nice, un-chaotic pockets of white, male and straight subjecthood, and are therefore intimately linked to their bodies, this forfeiture is a luxury that cannot be attained. As Cameron Bailey writes, “the process [of giving up their bodies] is neither universally simple nor universally desirable.”[iii] Instead, starting in the 1990s and continuing to this day, marginalized bodies have started to imagine ways of disrupting the smooth dis-embodied space of the virtual and re-affirming their “digitalia”, a term Bailey offers to speak of the convergence of genitalia, marginalia and wires.[iv]

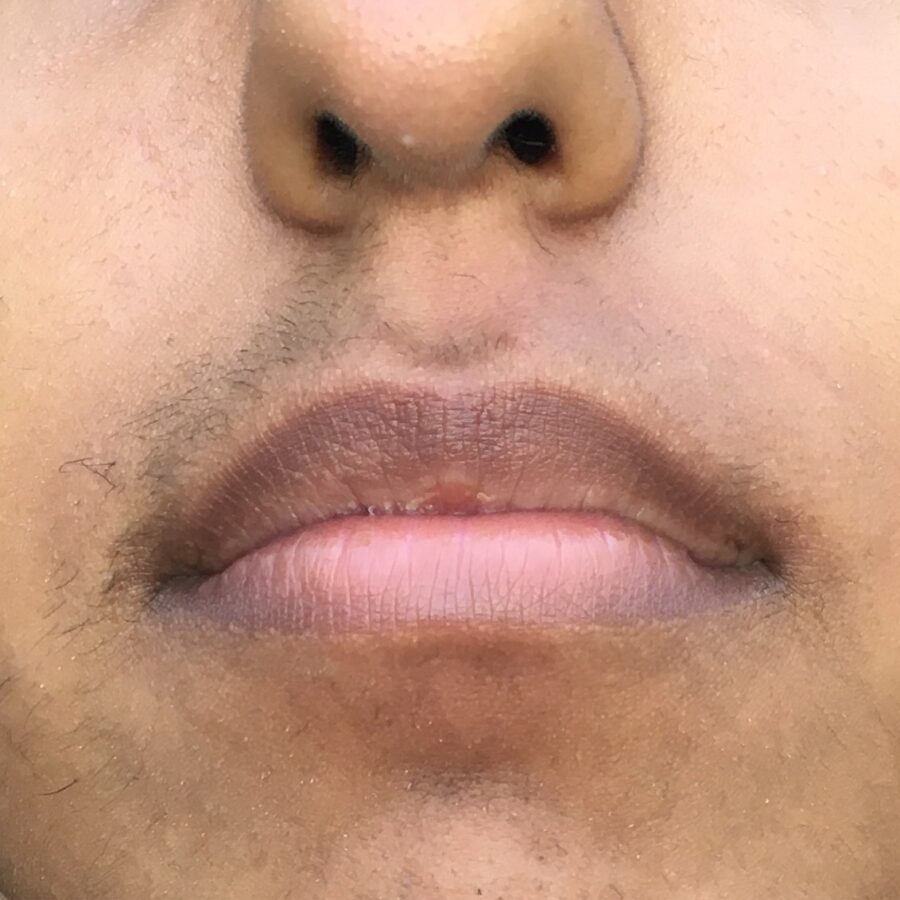

Enter the digital art practices of South Asian diasporic bodies. One of the most interesting artists to visualize her own “digitalia” is Ayqa Khan. Publishing her work primarily through Instagram, the American artist has used her body as a canvas to contest the racist and gendered framework of the Internet, and lay claim to her cybersubjectivity. In an untitled work of art captioned “balance baby” on Instagram, the artist has used a zoomed-in, borderless photograph of her upper lip to transport her real life experience into the virtual. And her real life experience is not solely hinged to her brownness or hairiness, as some have simplified in the past. Her experience is also home to a diasporicness, or in-betweeness—a constant tension that exists in the body. In “balance baby,” Khan wavers between body hair removal and body hair positivity, knowing that each side is always being negotiated along lines that have been decided by somebody else. Thus, the very act of making this photograph public becomes the tool for radical presence and “balance baby” comes to serve as a symbol for the ways in which marginalized subjects enter virtual spaces. For us, it is always a balancing act to put our bodies on virtual display and acknowledge the ways in which we are still, and may always be, tied to our bodies.

However, it is important to note that even as Khan and her contemporaries use Instagram, Tumblr and other social platforms to reroute the essentially racist and neutralized platform, there are counter forces at play that make their embodied presence precarious. Rightwing, neo-fascist and neo-Nazi congregations, such as Stormfront (which originated as a BBS group in the 1990s) and the more recent Daily Storm, have steadily increased their presence online in an effort to re-assert their own claim to the participatory culture of the Internet.[v] Despite their charged threats against other virtual and real communities, their claims to the space are being protected by The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), self-administered protectors of net neutrality that claim, “Any tactic used now to silence neo-Nazis will soon be used against others, including people whose opinions we agree with.”[vi]

The MCI and the EFF demonstrate that the Internet was cultivated on a utopic bedrock, which would be much happier with our neutrality than our realities. In knowledge of this system, we must continue creating space for ourselves and our unique sets of “digitalia”. And, while we may be presently stuck in a place that is neither here nor there, I am hopeful that even with these slow steps we are leaving Utopia behind.

Noor Bhangu is an emerging curator interested in exploring diasporic-centric art histories and conversations.

Allucquère Rosanne Stone, “Will the Real Body Stand Up?” in 9780262521772, ed. Michael Benedikt (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991), 81-118.

[ii] Media Control Interface, “Anthem,” YouTube Advertisement, 1991, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ioVMoeCbrig.

[iii] Cameron Bailey, “Virtual Skin: Articulating Race in Cyberspace,” in Reading Digital Culture, ed. David Trend (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001).

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Richard Kahn and Douglas M. Kellner, “Oppositional Politics and the Internet: A Critical/Reconstructive Approach,” in Media and Cultural Studies, ed. Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas M. Kellner (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 597-613.

[vi] RT International, “Net neutrality group fights ban of neo-Nazi internet site,” https://www.rt.com/usa/400190-net-neutrality-group-supports-supremacists/.