What Was Denied Us: Reconstituting Memory with the Bodily Drawn Mark by Dunja Kovačević

“I Don’t Know This Place” was, for me, the most haunting pencil drawing found in Matea Radić’s solo show, 7, at Graffiti Gallery last winter. The mixed media works contained in the exhibition represented the first attempt by Radić, whose childhood in Sarajevo was eclipsed by the siege, to grapple with this wound creatively. “I Don’t Know This Place” featured the artist as a girl, staring mouth agape in wonder or perhaps horror, partially out of frame. Her mother sits heavily on the ground behind her. The negative space surrounding them lacks the topographic specificity that a photo usually transmits, but the large, saucer-like eyes of a child who has seen too much and the resigned slump of a mother who knows it radiate with an emotional exactness. As a child during that same war, I recognized it instantly. It embodied the experience of dislocation and the clamour of unfamiliarity that can be deafening.

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag questions the assumed primacy of the photograph as a form of visual witness and the presumption that photographs are taken, while drawings are created. She reminds the reader that a photograph “cannot be simply a transparency of something that happened,” as it is always already chronologically framed and “to frame is to exclude” (Sontag 46). While drawing also frames, its “handedness” and physicality draw attention to itself as a mediated form whose perspective is etched into every line.

Sometimes representation by way of reproduction cannot do enough to wrestle with the largeness of trauma. Comics scholar Hillary Chute argues that the made mark contains the ability to materialize and make corporeal traumatic history. By attempting to bring it into view, this mark challenges the erasure and elision typically associated with traumatic memory. Trauma resists witnessing. Drawing invites it.

Graphic novelist Nina Bunjevac is a Serbian, Canadian-born artist, who fled back to Yugoslavia in 1975 as a child with her mother because her father was engaged in terrorist activities that eventually took his life. In her breakout book Fatherland: A Family History, Bunjevac attempts to weave together a fragmented familial and cultural history, fixing and grafting them side-by-side in time as a material object. No matter what has occurred, in this way they are together again.

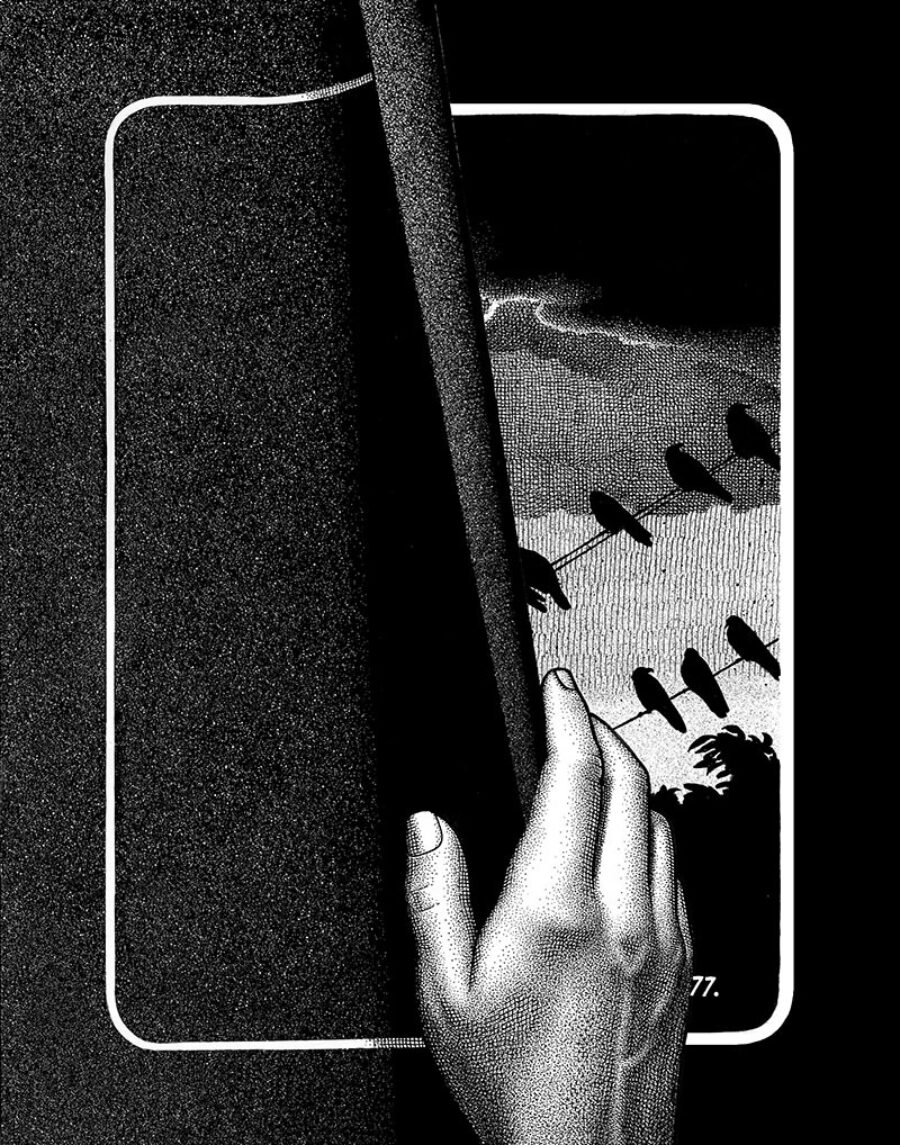

The drawn mark contains the trace of the body that produced it. At the end of the first page, we see Bunjevac’s hand sketching and redrawing the daughter's life. Chapters are bookended by liquid black pages broken up by pinhole images—a nest containing three eggs, an international flight—that tell another story within this story: that of children surfing the tides of historical and intimate family horror.

The structure jumps from the present to the past, to an even deeper family history and then to a broad geographical/political overview before returning to the present. It is a logical means of addressing memory gaps and elision, neatly segmenting where her story intersects with her father’s and where that bloodline is severed. Bunjevac works to witness his final days, those without a witness. In doing so, she is drawing on the blank spaces of her past, going beyond the pinhole scope of her own memory. She legitimizes this account, willing it into existence by rendering it with and through her body. Is it any less real, this crafted memory? Is it not just another practice of memory, that of post-memory?

Graphic artist Keiji Nakazawa, who illustrated Barefoot Gen loosely based on his experiences as a Hiroshima survivor, claimed, “when I was drawing ... the stench of rotting bodies returned to me” (Chute 117). There is a profound link between our memories and the senses through which we form them. While perhaps not consistently reliable, memory risks fading without them.

It is precisely the unreality of drawing that can render it more faithful to the affective register of memory. It is of both the mind and the body. Radić's cartoonish proportions are somehow more true to the experience of adulthood and war from the perspective of a child. Bunjevac, too, speaks to us from eye level. She is able to stitch together the historical past and private history by shifting between archival documents and the murkier waters of memory.

We are always in the act of redrawing the past. Every attempt at recall is an act of rewriting on the ashes. We draw our own archive when history and circumstance have denied us one.

References:

Bunjevac, Nina. Fatherland. Picador: 2012

Chute, Hillary. Disaster Drawn. Harvard UP: 2016.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. Picador: 2003.

Dunja Kovačević is an emerging critic and editor living in Winnipeg on Treaty 1 territory. She holds an MA in Cultural Studies from the University of Winnipeg, sits on the board of the North Point Douglas Women's Centre and is a co-founder of Dear Journal, an annual feminist print anthology.