Art and Disability: The Political Power of Decorating Assistive Technology by Baden Gaeke Franz

In 2017, my left wrist started to hurt. In November, it hurt so much that I had to buy a wrist brace. By March, I was so tired of wearing the ugly brace that I decided to make it more beautiful. So, I broke out the acrylics and I painted Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night on it. I thought what I was doing was making the best of a bad situation. If I had to wear this brace, at least it could be beautiful. What I didn’t expect was that in painting the brace I would completely change the way other people interacted with my disability, as well as how I thought of my own disabled embodiment.

When I first started wearing my wrist brace, strangers would ask me how I hurt my arm. Not wanting to be rude by refusing to answer, I was left explaining my family’s history of weak joints to people who had no business knowing my family’s medical history. This lack of privacy is disturbingly common for people with visible disabilities; strangers feel entitled to a discussion about their disability (Pullin). These conversations are often pathologizing or pitying, dehumanizing disabled people and reducing us to our disability.

After painting my wrist brace, the first question people asked changed from “What happened to your arm?” to “Where did you get that cool brace?” This led to conversations centred on me as an individual and my artistic skill, rather than them seeing me as an object of the medical system or a passive sufferer. These interactions changed from a medical model of disability to a social model, in which I was a whole person and my disability was part of that. By painting my brace, I invited people to interact with my disability on my terms, rather than on the terms of the dominant culture.

I am not the first to notice this phenomenon. In an article she co-wrote with Diane Driedger, Nancy Hansen describes similar experiences after painting her crutches red with disability rights slogans written on them. When she uses her painted crutches, strangers often come up to her and ask to read the writing or compliment her on their appearance. According to Hansen and Driedger, “these comments were very positive as opposed to them making no comment or a negative comment about the everyday crutches.” The painted crutches “quite literally changed attitudes, and generated confidence, conversation, communication and change” (Hansen and Driedger, 300).

A common trend in assistive technology is to make it as inconspicuous as possible. This can be seen in the miniaturization of hearing aids or the push to make prosthetic limbs appear as close to a biological human leg as possible (Pullin, 23). These technologies work to normalize the disabled body. They attempt to eliminate the stigma of disability on an individual level by making their users appear less disabled. However, in seeking to distance the individual from their disability, they only reinforce the structures that keep disabled people oppressed. By hiding disabled embodiment, they imply that disability is inherently shameful and ought to be hidden. This shame is then often internalized by disabled people, who do not feel confident about their disability and therefore continue to hide it.

The decorated device breaks this cycle. By refusing to hide, decorated assistive technologies transform disability from a point of shame to a point of pride, claiming disability as something beautiful: not a defect, but an opportunity to re-design the body and to express personality. It opens a conversation about disability, inviting people to look at and interact with disability in ways that undecorated devices do not. Thus, decorating assistive technology is not just an aesthetic choice, but a political one with the power to shape the ways in which people with disabilities are viewed in society. On this and so many levels, art is powerful, opening the viewer to question, to rethink and to change.

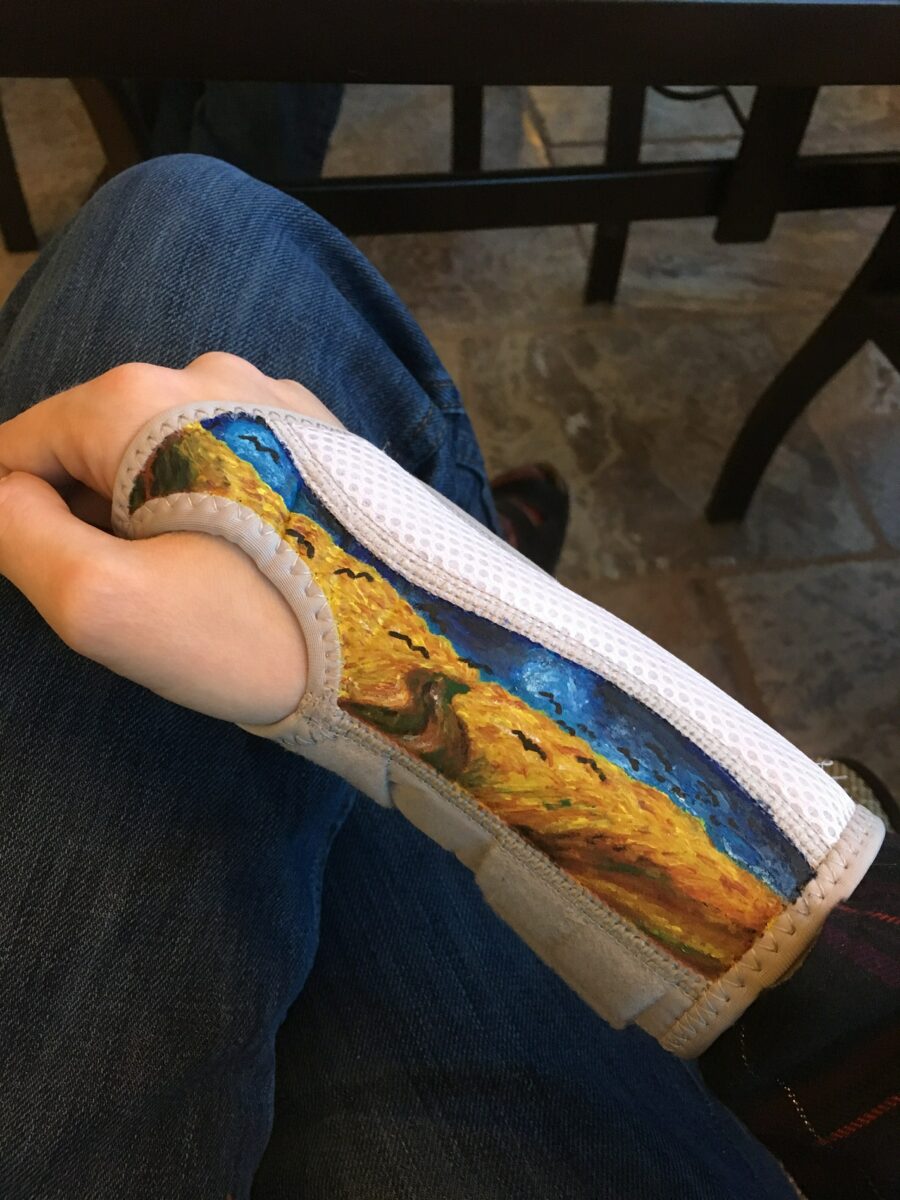

A few months ago, I started to have pain in my right wrist as well and I had to buy a second brace. This time I didn’t hesitate to paint another Van Gogh piece on it: Wheatfield with Crows. Rather than the defeat I had felt buying my first brace, I felt excitement and pride as I bought the second. Painting my braces has given me confidence in my disability, opening conversations about what constitutes a normal body. In my life and the lives of many others, decorating assistive technology has been not only beautiful, but radically political.

Hansen, Nancy E. and Diane Driedger. “Art, Sticks and Politics.” Living the Edges: A Disabled Women’s Reader, edited by Diane Driedger, INANNA Publications and Education Inc., 2010, pp. 295-303.

Pullin, Graham. “Fashion meets Discretion.” Design Meets Disability, MIT Press, 2009, pp.13-38.

Baden Gaeke Franz is a disability advocate living in Winnipeg. They are a student at the University of Winnipeg, majoring in Women's and Gender Studies with a minor in Disability Studies and Human Rights. Gaeke Franz was MAWA’s Practicum Student in the winter of 2019 and the leader of RavelUtion, MAWA’s Young Queer and Feminist Knitting Group.