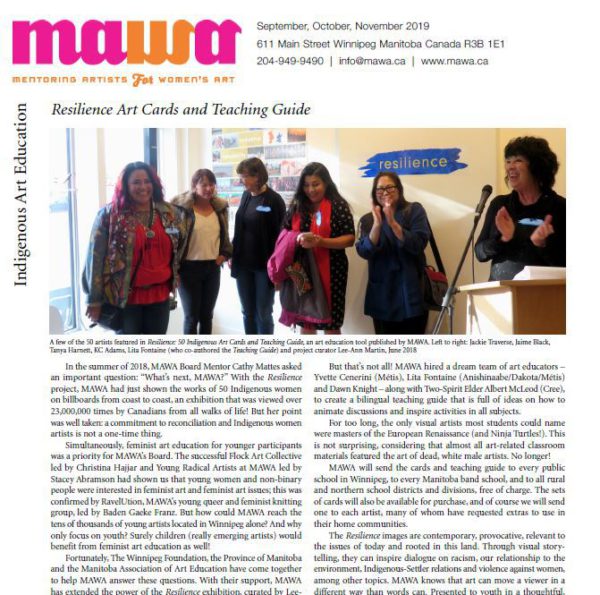

Time-Based Nuclear Meditations in the 21st century – where have we been, where are we going?

by Andrea Terry

Since the mid-1940s, photography has helped shape public understandings of nuclear weapons and energy. Images documented the 1945 bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the 1986 Chernobyl and 2011 Fukushima Daiichi meltdowns. Nuclear voyeurism has included photojournalism, surveillance, propaganda and – somewhat surprisingly – tourism. Artists, too, have made compelling images based on our nuclear past and present, but more often than not they encourage viewers to move past the “shock and awe” of the “atomic picturesque”[1] and meditate on the ongoing so-called “legacies” of the atomic age.

By the late 1970s, women had become so vocal in the anti-nuclear movement that sociologist and Cornell University professor Dorothy Nelkin published the 1981 article “Nuclear Power as a Feminist Issue.” In her exploration of the wide-ranging socio-political factors that propel organizations and individuals, Nelkin is quick to point out that this movement “begins with the special effects radiation has on the health of women and on future generations.”[2]

For those with Baby Boomer parents such as myself, who came of age after the Cold War’s demise, Alison Davis’s animated short film Loving the Bomb (2009) links experiences of the 1950s with more recent memories. When I was in grade school, I asked my dad (presumably motivated by a class assignment) what he remembered most from when he was my age. Surprisingly, he described the routine “Duck and Cover” drills he performed with his classmates in Ottawa. Davis’s film locates these exercises within a larger context. Featured in the fifth annual International Uranium Film Festival program in Quebec City, in 2015, the 4-minute short follows the quotidian experiences of a “nuclear” family (father, mother and son) who live near a nuclear arms testing site, the father’s workplace.[3] The boy ducks and covers at home and school, which seemingly drives him to build a play fort with a sign atop the entryway that reads “BOMB PROOF.” Following the father’s death in an atomic explosion, the mother and son struggle to cope with both the loss and radiation effects. Davis’s work calls attention to the gendered dynamics of the nuclear age in the 1950s, particularly how women and children grappled with the consequences of atomic power.

In spring 2019, Mary Kavanagh’s solo exhibition Daughters of Uranium opened at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery in Lethbridge, Alberta. Her two-channel video projection Trinity focusses on her experience, filmic observations and interviews at the Trinity test site in Alamogordo, New Mexico. Located on the White Sands Missile Base and owned by the US military, the site is open to tourists 18 years of age and over (with required identification) for self-guided “open house” events only on the first Saturdays in April and October.[4] At points in Kavanagh’s film, individuals – identified by name, occupation and place of residence with captions – speak directly to the camera, articulating their reasons for visiting. These accounts draw in viewers, compelling them to appreciate the diverse motivations that have given rise to nuclear tourism destinations – sites around the world where nuclear weapons and power are manufactured and weapons have been detonated. Moreover, these declarations call attention to contemporary atomic anxieties.[5]

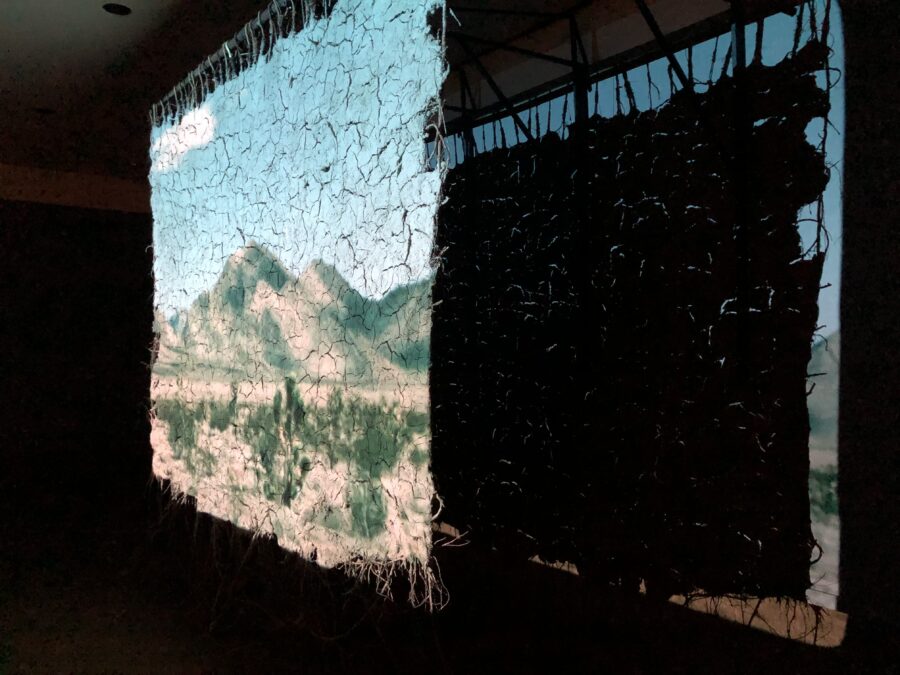

Andrea Pinheiro compiled footage from her year-long exploration of nuclear and geographically significant sites for her exhibition Shattered basin, fired thing at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery. While onsite, she installed a metal framework and crafted a screen made from dried clay and woven spruce roots that she gathered from the Goulais River near Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. Onto this surface she projected a 16 mm looped film. Landscapes as varied as Trinity, the Petrified Forest in Arizona’s Painted Desert, the US government’s nuclear Nevada test site and writhing river rapids flicker across the cracked earth panel – stunning aberrant vistas both natural and manufactured. By examining multiple landscapes over time, the installation invites reflection on land use, responsibility and ownership. This film takes up where nuclear photography – spectacular snapshots isolating singular moments – arguably leaves off. Pinheiro’s film projects images onto land, bringing together places and events prominent in the past with present-day global concerns, including nuclear weapons production, toxic waste disposal and climate change.

Collectively, the artworks of Davis, Kavanagh and Pinheiro urge viewers to slow down and reflect, to consider how we all got to this point in time. In an age where communicative technologies, social media and our “smart” devices have conditioned many to expect/demand instant gratification, taking time to look back and think carefully about how to move forward is time well spent.

Andrea Terry, PhD, is an independent curator, writer and art historian who teaches in the Department of Visual Arts at Lakehead University. Her most recent book, Mary Hiester Reid (1854-1921), was published by the Art Canada Institute / Institut de l’art canadien in September 2019.

----

[1] John O’Brian, “Nuclear Flowers of Hell,” Camera Atomica (Art Gallery of Ontario and black dog publishing, 2015) 96.

[2] Dorothy Nelkin, “Nuclear Power as a Feminist Issue,” Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 23.1 (January 1981): 15.

[3] Alison Davis, “Loving the Bomb 2009 / 4 minutes / 16mm / Animation,” Alison Davis, animator & artist, http://alisondavis.ca/animation#ltb

[4] The first “open house” event was held in September 1953, and approximately 650 people attended. https://www.wsmr.army.mil/Trinity/Pages/TrinityHistory.aspx.

[5] Mary Kavanagh, “03_Kavanagh_Trinity_Preview_2019,” Vimeo, https://vimeo.com/289405123.