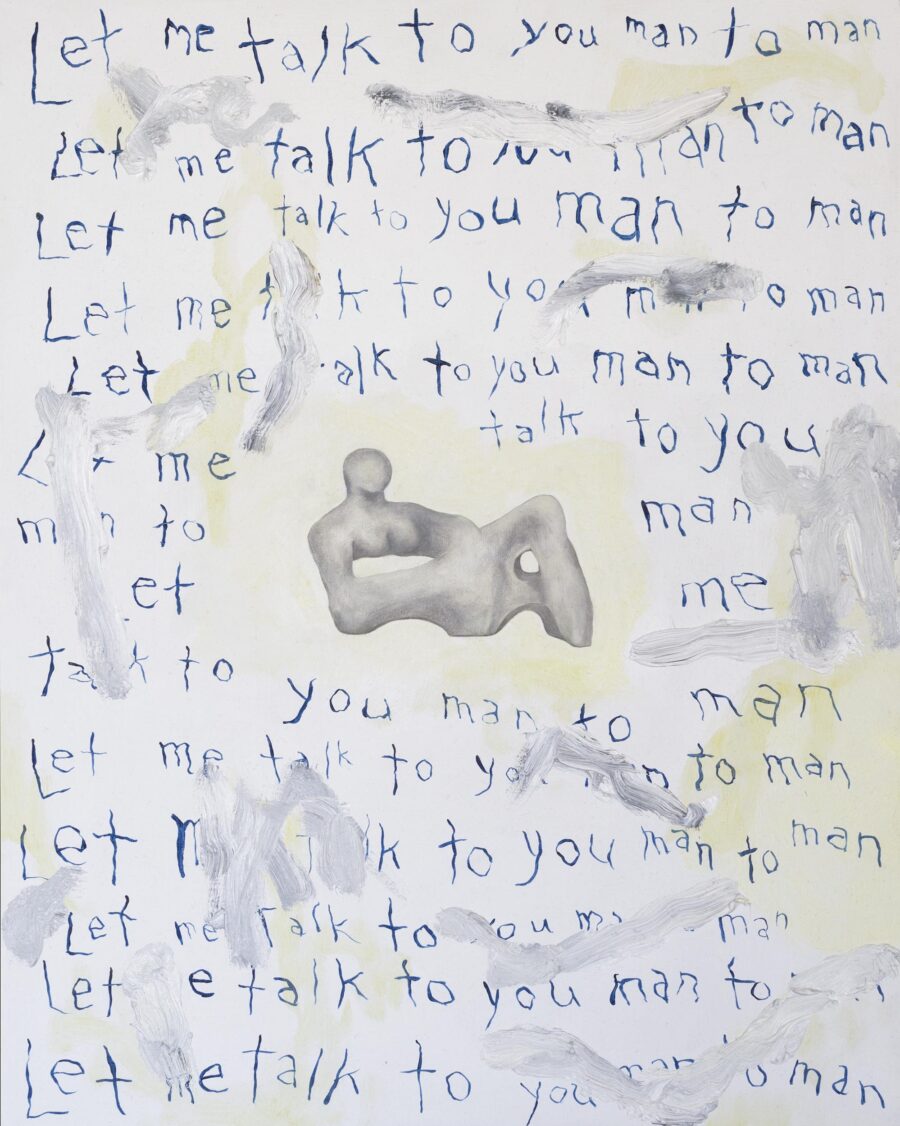

Erica Mendritzki, New Contract, oil on wood panel, 2015

Metaphors for Brawn & Brain: Some Thoughts on Art Writing

by Sarah Swan

Like you, I have an overcrowded brain. Important subjects jostle for space with serious concerns, not to mention profound amounts of mental detritus created by social media.

“The Empty Brain,” an essay by research psychologist Robert Epstein, describes this strangely comforting fact: our brains don’t contain what we think they do. They don’t store memories, don’t record visual stimuli, don’t transfer or retrieve information. Given this reality, Epstein asks, why do so many scientists talk about our mental life as if we were computers? Part of his answer is language. We tend to describe cognition in the terms of new or dominant technology. (My mind just isn’t operating well today. I’ve been stuck on this problem but the wheels are starting to turn.)

Cognitive linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson call brain = machine a “metaphor we live by.” In their numerous publications, they write about metaphors as culturally and cognitively fundamental, as determining how we live. Besides brain = machine, Lakoff and Johnson elaborate on other metaphors like argument = war (She shot down my argument. Your claims are indefensible), and theory = building (Is that the foundation of your theory? You need to construct a stronger framework).

In her essay “Woven into the Fabric of the Text: Subversive Material Metaphors in Academic Writing,” Dr. Katie Collins proposes a shift in our thinking, from theories as buildings to theories as fabrics. Buildings offer a sense of power, progress and control—characteristics, writes Collins, of conventional masculinity. Quilting metaphors on the other hand, like stitching, sewing and piecing, are a way of recognizing contribution, de-centered activity and female voice.

I feel a degree of comfort when reading Collins. Theories, for her, are warm rather than cold. Creating tapestries of thought feels relational, inviting. But I also feel resistance. I like building and construction metaphors for their real and figurative qualities—the solid heft that bricks have, the sweat and effort it takes to assert verticality, and, conversely, the joy of the wrecking ball. I like fighting metaphors too. Momus founder Sky Goodden’s advice to aspiring art critics is “Take a position!” (Argument = war.)

As an emerging art writer, I enjoy studying established writers—their unique ways of translating the visual into the written, their relationship to jargon, level of bombast. The writers I admire most know how to turn a figurative phrase, and their metaphors are as generative as the art they are attempting to describe. Often, they are admittedly contradictory, and follow the chaotic, haphazard leaping of associational thoughts. In their thinking about art, brain ≠ machine, brain = body. It is a flagrantly rebellious sense organ. Sky Goodden also says “Put some skin into it!”

There are varied reasons why people love art, but chief among them, I think, is the vertigo. When walking through any half-decent group show, we feel the gravitational push and pull of each artist’s work. Sometimes, we feel the floor slant. With the good art, the great art, we feel a full brain/body swoon.

There are artists whose work conjoins, at least by way of Katie Collin’s thinking, contradictory metaphors. Bev Pike paints ropey, visceral architecture, great columns of entwined clothes. Barb Hunt knits land mines out of pink wool, embroiders on worn army fatigues. While Pike creates entirely female worlds, much of Hunt’s work infiltrates “male” territory. Both artists’ work has a bolstering, stabilizing effect on the psyche, allowing me, however briefly, to feel in full command of female strength, aggression, ego. Dear captains, I salute you!

Conversely, the jaundice-toned paintings of Erica Mendritzki are destabilizing. “Let Me Talk To You Man To Man” reads a Mendritzki text painting, the letters pleading, angry, trembling. Her work allows me to admit how shaky I am. If we have made progress, fellow feminists, why do I feel so queasy?

In “The Empty Brain,” Epstein describes how he asked researchers to describe human cognition without using computer or machine metaphors. They couldn’t do it. This, I think, is a job for figurative language.

The brain is a Mendritzki painting. It’s a quivering, spongy mass, by turns hot and cold, prickly and velvety. It is a steaming soup, a porcelain globe, an axe with a bloodstained blade, a lump of clay pressed upon by rejections and defeats. It is an ancient Gordian knot, capable of great rational feats and the deepest intellectual deceptions. For better or worse it leads us. Brain = maniac, brain = wanderer.

Sarah Swan is a freelance art writer from Winnipeg.