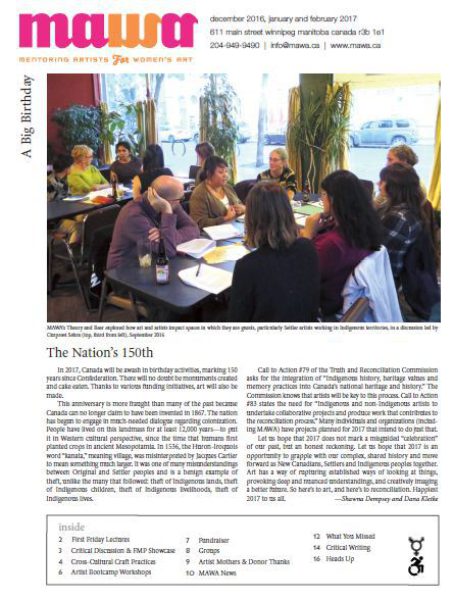

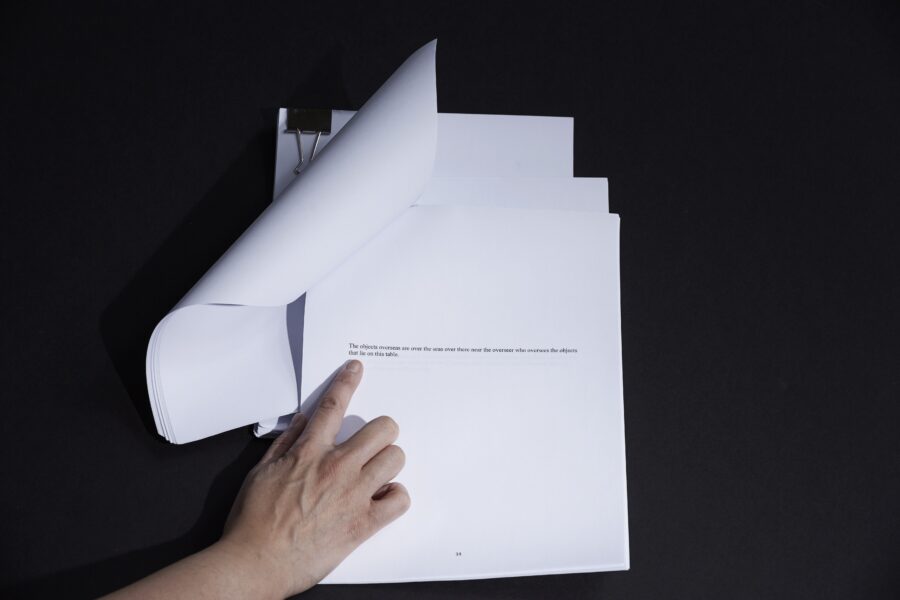

and now to begin as if to begin begin of beginning again and again and again (in the continuous present with Gertrude Stein), detail of Part II, artist book, 2016. Documentation by: Daniel Ehrenworth.

On Working with Gertrude Stein

by Erika DeFreitas

As if to begin was the beginning of again.

I have been preoccupied with feelings of loss and even anticipated loss, primarily the loss of a loved one. This has been an on-going theme in my artistic practice for the past ten years. Ten years. I remember hearing somewhere that it takes ten years to master a skill, so one might assume that after ten years of immersing and entangling myself in this work, I would be somewhat confident and well versed in strategies for working through loss. The truth is, I have not. I have not found “a solution” but rather an unending visual language that addresses these complicated feelings, based on the culturally complex, multifaceted terrain of practices, rites and rituals involved in the act of mourning. In recent years, this journey has naturally led to an increasing interest in the afterlife.

The Work of Mourning is a compilation of eulogies and funeral orations written by French philosopher Jacques Derrida in memory of his contemporaries. One question that I’ve extrapolated from this book is, how do we allow the dead to have agency? To have a voice? In his writing, Derrida accomplished this by using the words of those he is speaking about—words that they have said about death and mourning. Following this line of questioning, I started to work with a psychic medium to help create a bridge between myself and artists who have passed. One such experience has led to a collaboration between myself and the late writer and patron Gertrude Stein. As I work with Stein and as Stein works through me, I consider the act of embodiment and disembodiment and wonder if my body has become without a boundary, all while questioning the implications of these notions on my sense of self.

One work that Stein and I have collaborated on is a series of seven artist books called, and now to begin as if to begin begin of beginning again and again and again (in the continuous present with Gertrude Stein). These artist books begin as a record of not only working through and interrogating Stein’s play, Objects Lie on a Table, but a continued critique of conventional writing, including colonial and patriarchal ways of communication. In the series, proper sentence structure, use of punctuation and linear writing all become turned into themselves—tools for rewriting writing. The first four books focus on different aspects of Stein’s play: the nuns, the Negros and Chinamen, objects in the house and the concept of time-sense. The fifth book is an excerpt from a discussion between myself and Stein that was mediated by a psychic medium. Books six and seven are about arrangements, compositions and the “still-life.”

My sense of self shifted while in discussion with Stein, specifically when I asked her if she would like to collaborate with me and her response was that she already has been. I knew then that she was with me in those moments when I felt a sudden push to continue, when a flood of words entered my mind and I couldn’t help but let them pour out from the tips of my fingers onto the keys of the keyboard. It was in these moments that we were working together, in these moments when I thought that I had briefly met a stroke of genius that was buried deep within my being and I had yet to discover. It’s okay to chuckle at this; in hindsight I, too, chuckle because I know that this is all a part of Stein’s dark yet playful sense of humour seeping out.

When starting to write about this experience a friend of mine suggested I read about Affect Theory, which essentially is a theory about bodily experience. This seemed an apt approach in my attempt to understand the multitude of conflicted feelings that arose during this collaboration with Stein. In my research I came across a quote from Gilles Deleuze, another French philosopher, who wrote that “a body affects other bodies, or is affected by other bodies; it is this capacity for affecting and being affected that also defines a body in its individuality.” In working with Stein there were moments when my body—my vessel—became porous and without a perceivable outline, a boundless entity that was transgressed without my full awareness.

What I have come to understand is that my body has been affected by another entity who is without a body. Stein and I both exist in a state of the in-between and because of this we are in a space that allows for us to communicate with each other in ways that challenge all sorts of convention. As a result, I have many questions that I now entertain as Stein and I work on parts eight through ten of our artist book series, the most pressing of which is this: is there a line that separates where I end and Stein begins?

Exploration through an inquiry-based model is an act that as artists we often engage in. However, it is likely that when one chooses to participate in artistic practices that circumvent traditional modes of working, these processes may be labelled “eccentric” or “outsider art.” There is a history in the Arts, Black culture and Feminism of cultural producers embracing the spiritual in their practices and having their rich contributions dismissed because of this. I am just one artist out of many who has chosen to explore an alternate path in a search for inspiration and collaboration. I am well aware that my process may be too challenging for others to understand, but I am certain that my work with Stein is a worthy contribution to this archive of visual language I am in pursuit of.

Erika DeFreitas is a Toronto-based multidisciplinary conceptual artist. Her work can be seen at: www.erikadefreitas.com.

Deleuze, Gilles (1988), Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, translated by Robert Hurley, San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books.