Tapestry of Spirit: Stitching as an act of re-enchantment by Helene Vosters

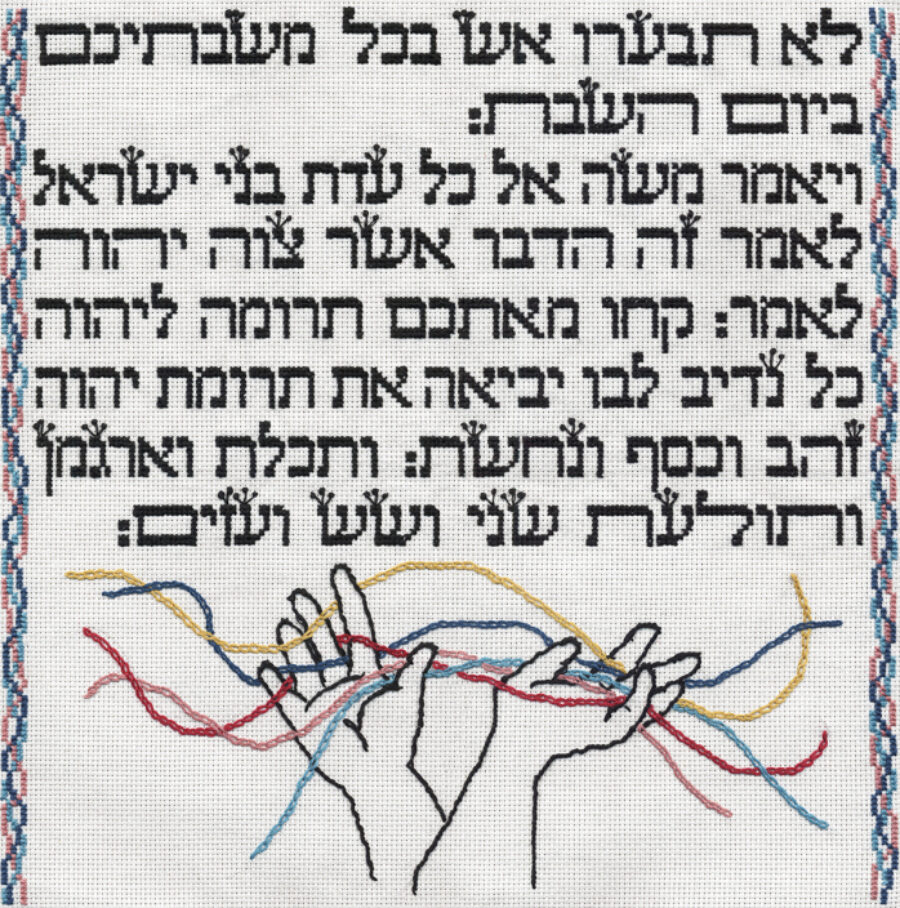

At a recent visit to Toronto’s Textile Museum (one of my favourite haunts), I came upon Tapestry of Spirit: The Torah Stitch by Stitch Project, a monumental cross-stitch work collectively crafted under the creative leadership of textile artist Temma Gentles. With Tapestry, Gentles does more than celebrate the spiritual texts that form the content of the work — the first five books of the Bible alongside selections from the Qur’an and the Christian Scriptures. She also pays homage to over 1,400 volunteer stitchers from 46 countries who collectively laboured for more than 140,000 hours to produce project’s 1,464 panels.

Organized into four-verse vertical sections, the panels of the exhibition have been painstakingly sewn together to form a continuous scroll-like display that winds its way through ten of the museum’s galleries. Interspersed among the panels of text are hundreds of smaller illuminations bearing individual stitchers’ creative interpretations of the text.

As a queer, monolingual-Anglo, non-Jewish, pagan-leaning, feminist artist-scholar, the cross-stitched text of the Hebrew (Torah), Arabic (Qur’an) and Greek (Scriptures) panels are largely incomprehensible to me except through the information cards that run along the bottom of the scroll and offer a brief synopsis of the vertical sections they accompany. It is their materiality and the process of making that captures my imagination. As arts scholar Paula Owen writes, “The object links us to thoughts, memories, sensations, histories and relationships, rather than being an end in itself with a predetermined meaning. It is instead a catalyst for any number of unpredictable effects.”1 Sitting amidst the hundreds of thousands of stitches, inscribed with the everyday — familiar materials and durational labours — Tapestry sings like a hissing chorus of thread through cloth messages of spirit, memory, celebration and resistance.

Tapestry’s collectivized and cumulative stitch-by-stitch-by-stitch-by-stitch-by-stitch… reverberates with centuries-long struggles by women and their allies of many faiths to have their voices included within orthodox religious structures and institutions, stirring memories of my discontent growing up as a girl in the Catholic faith. Tapestry’s place in this lineage of struggle dates back to 2013, when Gentles launched the project as a creative response to being excluded from an exhibition of women’s religious art in Israel on the grounds that it was for Orthodox women only. Gentles brilliantly refused this rejection by extending an affirming invitation to anyone of any faith (or gender) who wished to engage with the Torah through the act of stitching its verses.

The project’s steadfast stitch-by-stitch-by-stitch-by-stitch-by-stitch… hums with histories of women’s affective and material labours of care. A monument to women’s contributions to gift economies, Tapestry offers a glimpse into the everyday generosities of the affective labour that goes into crafting. Each stitch is a gesture toward the millions of hands that sew, knit, bead and crochet and then give away objects of comfort and care, sweaters, scarves, moccasins, afghans.

Though its content is focused on the production of spiritual documents from Abrahamic faiths, Tapestry points to a myriad of collectively crafted tapestries of spirit, memory and resistance — Christie Belcourt’s Walking With Our Sisters and its 1,763+ pairs of vamps beaded in memory of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls; Marianne Jorgensen’s Pink Tank constructed of 4,000 pink squares knitted and crocheted by a transnational collective of volunteers as a protest against involvement in the Iraq War; or the thousands of handkerchiefs of Bordados por la Paz (Embroidery for Peace) embroidered by families and communities in memory of the missing and murdered in Mexico.

Like many feminist artists, I am caught in the tension between the struggle for women’s right to be compensated for their creative and affective labours and a respect for the role that women’s unmonetized craft plays in stitching tapestries of refusal to the demoralizing and disenchanting effects of capitalism’s intersecting logics of commodification, exploitation and extractivism. Tapestry’s spirit extends beyond the textured, faith-based texts of the exhibition. It lives through the generosity of its many makers, whose inter(in)animating threaded labours stitch a tapestry of re-enchantment across place and time.2

1 Owen, Paula. “Fabrication and Encounter: When Content is a Verb.” Extra/ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, edited by Maria Elena Buszek (London: Duke University Press, 2011), 84.

2 See Rebecca Schneider. Performing Remains, (New York: Routledge, 2011). Combining Fred Moten’s notion of intermedial inter-inanamation with Elizabeth Freeman’s “temporal drag,” or queerly syncopated time, Schneider proposes that time’s cross-temporal slippages produce moments through which material and immaterial remains engage in a “cross- or intra-temporal negotiation, even (perhaps) interaction or inter(in)animation of one time with another time” (30–1).

Helene Vosters is an artist-scholar-activist whose work focusses on issues of state violence, social memory, and the role of performance and aesthetic practices in mobilizing engagement. A multi-disciplinary artist—performance, craft and relational arts—Vosters utilizes a task-based labour aesthetic in her practice. She is the author of Unbecoming Nationalism: From Commemoration to Redress in Canada.